On Thursday I visited the New England factory where my shirts are being sewn, and I’m still on a high from the experience.

This is John in front of one of their super long cutting tables. He’s been a pattern maker with this factory for 40 years.

The grader that I wrote about here sent a disc with my graded patterns to John. The disc shows how the pattern pieces should be arranged to avoid any fabric waste. This arrangement is called a marker (because, before computers, it was how the fabric was marked for cutting).

This machine prints out the markers.

Here, a machine is spreading the fabric on a cutting table.

This computerized cutter is cutting the fabric according to the markers.

Next, employees match the fabric pattern pieces to the paper versions to ensure that a size 4 sleeve won’t be sewn to a size 10 bodice. Each fabric piece is bundled with the rest of the pieces for that shirt and sent downstairs to the sewing floor. See what happens on the sewing floor after the jump.

Harvey, the factory’s engineer, explained to me that each part of the shirt is worked on in a cell. This is a new development. Previously, each worker specialized in only one sewing specialty. The shirts moved in a line from one specialist to the next (called a traditional line flow). If the sleeve specialist was out sick, the shirt couldn’t move forward until she returned. Everyone in the line before the sleeve specialist kept working, creating a bottleneck. Everyone in the line after the sleeve specialist sat around waiting for her to get back.

With the cell system, every sewer has multiple specialties. It took months to retrain the employees to be able to perform multiple tasks, and the fastest specialists refused the training. They only wanted to work on their single specialty. So the company turned to their second tier sewers and made a fascinating discovery: their second tier sewers were actually the most flexible. They could be good at several tasks. This ended the bottleneck problem. It used to take 30-40 days to complete an order. Now, the target is 2.5 weeks.

Five workers work on 15 machines in the collar cell.

This is Cathy, the best sleeve sewer in the factory. She is also the “lead” in charge of everything on this side of the factory floor.

This is Melinda. She usually sews cuffs, but here she is sewing decorative tabs into shirt side seams because she is especially skilled at the difficult task of sewing angled lines that come together in a point.

This is Albert, one of the factory’s problem solvers. Before accepting my job, Albert, Harvey and John met as a team with the company owner to determine whether they could produce my pattern.

The slit in my shirt sleeves was especially challenging. Here, Albert is showing me that they were able to hide all the raw edges. This had been an issue in earlier samples, and it’s a great relief that they have figured out how to address it.

In this cell, the sewers are attaching the collars, sleeves and sides.

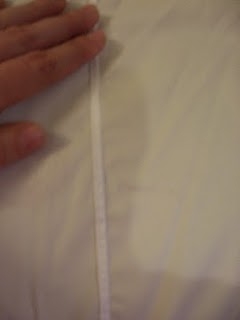

This sewer is sewing the French seams in one of my shirts.

Here’s a closeup of one of the French seams. The seams of whatever you’re wearing as you read this are probably finished with overlock stitching (also called merrowing because it was invented by the Merrow Machine Company in 1881). This is faster and requires less fabric. The seams in Anne Fontaine’s $200 shirts are merrowed. The seams in her $500 shirts are French. I’m told that women don’t really care about or notice this kind of detail, and I’m inclined to agree since I had never heard of French seams before I began this project. If you think about it, you’re more likely to get a stain on the shirt and throw it away before the merrowed seams ever wear out. It may ultimately prove cost-prohibitive to provide French seams at my $120 price point, but for now, it makes me feel smug to say that my shirts have them. [Feb. 2, 2011 Note: Since taking a seams and finishes class at FIT, I have learned that my shirts don’t have French seams, but another very sturdy kind of seam common to quality dress shirts.]

Harvey is holding up one of my shirts. This was my first time to see my label sewn into one of my shirts, and I was transfixed.

After all the pieces are sewn together, Maria sews the buttons on and inspects everything.

Next, the shirt goes to finishing where it is ironed and inspected again.

Finally, Louis packs the shirts for shipping. I love his perfectionism. He walked me through every decision I needed to make about packaging.

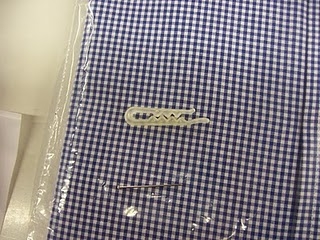

For instance, we’ll use clasps instead of pins to hold everything in place.

If you order a shirt and open the box, it’ll look just like the one below (except in a plastic sleeve).

The shirts should be shipped to me next Tuesday. I brought a size 14M shirt home with me and was delighted when I tried it on. Look for pictures of it in my next post!

Congratulations on your first production run, Darlene.

So very exciting.

Thanks, Marketa. I was so excited that I forgot that the correct term is "production run." And I also forgot to hold the camera still when I took some of these pictures.